Grapes first arrived to Peru in the 16th Century, brought from the  Canary

Islands by Marquis Francisco de Caravantes. According to chroniclers

from the era, the first vinification of South America took place in the

Marcahuasi Estate, in Cuzco. They also mention Mateo Atiquipa as the

first American enologist. However, it was in the valleys of Ica where

the crops reached their maximum expansion, favored by the area’s weather

conditions that also permitted the strong development of the wine

industry.

Canary

Islands by Marquis Francisco de Caravantes. According to chroniclers

from the era, the first vinification of South America took place in the

Marcahuasi Estate, in Cuzco. They also mention Mateo Atiquipa as the

first American enologist. However, it was in the valleys of Ica where

the crops reached their maximum expansion, favored by the area’s weather

conditions that also permitted the strong development of the wine

industry.

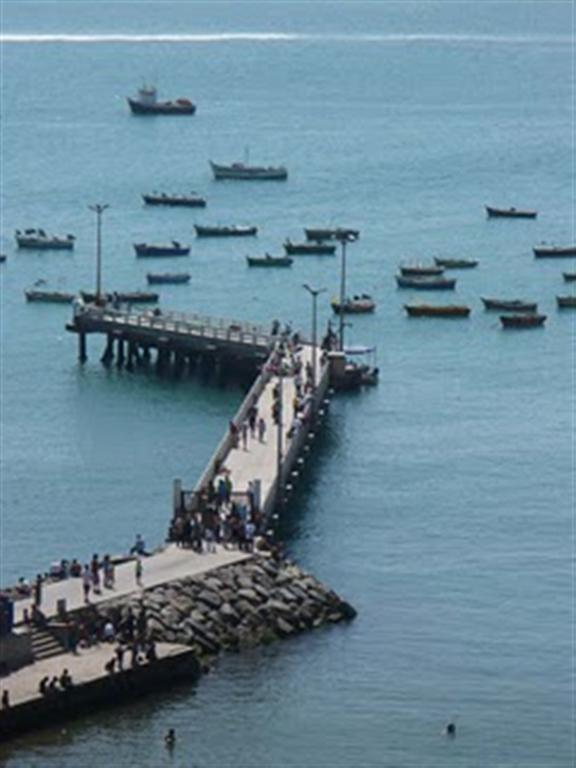

In the mid-16th Century (1574), the Spaniards began to use the name “Pisco” to refer to a river, a town and a port. This was one of the main regional trade routes where guano and Spain bound silver were shipped.

Vine crops were so successful in Peru that wine exports from the

Peruvian Viceroyalty to Spain became common, and Spanish producers

requested Philip II to ban such trade in order to avoid the threat of

competition. The ban was enforced in 1914, forcing coastal monk

landowners to intensify the production of the Peruvian grape eau-de-vie,

which quickly became a popular drink among the region's travelers

thanks to its unique characteristics.In the mid-16th Century (1574), the Spaniards began to use the name “Pisco” to refer to a river, a town and a port. This was one of the main regional trade routes where guano and Spain bound silver were shipped.

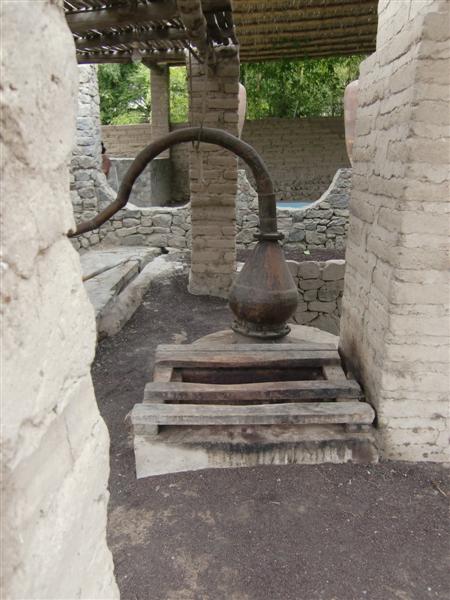

The earliest historical reference to the preparation of grape eau-de-vie dates back to the early 17th Century. Lorenzo Huertas, renown Peruvian historian, says: “We have found what might be the oldest reference to the preparation of (grape) eau-de-vie not only in Peru, but in America: a document from 1613 mentioning the manufacturing of this liquor in Ica.” The document mentioned by Huertas is the will of Pedro Manuel the Greek, resident of Ica, whose last will stated that, among his properties, he had a Creole slave and “thirty burnay jars filled with eau-de-vie, and a barrel filled with eau-de-vie, that contained thirty little pitchers of such liquor, plus a large lidded copper cauldron used to extract eau-de-vie, and two pultayas, one with a spout and the other smaller and in better conditions.” This is the oldest information found in Peru about eau-de-vie. However, warns Huertas, although the will is dated 1613, eau-de-vie production instruments were used in earlier years. (Research by Dr. Lorenzo Huertas Vallejos, Producción de Vinos y sus derivados en Ica, Siglos XVI y XVII [Production of wine and its byproducts in Ica, 16th and 17th Centuries], Lima, 1988.)

The "Diario del Perú" (“Peruvian Journal”) of Hugh S. Salvin is also worth mentioning. It refers to Pisco as a city “… built about a mile away from the beach, and laid out like all Peruvian cities: a large main square in the center and converging straight streets (…). This district is known by the manufacturing of a strong liquor named liked the city and distilled from grape in the fields toward the highlands, five or six leagues away.”

Similarly, the “Testimonio del Perú” study (“Peruvian Testimony”, 1838-1842) by Johann Takob Von Tschudi, reads: “… the small city of Pisco, half a league away there is a safe bay that offers good anchorage. Due to the exports of its eau-de-vie that has become quite significant… Grapes have excellent quality, and are juicy and very sweet. The eau-de-vie is distilled from most part of them and, unsurprisingly, it tastes delicious. All of Peru and a large part of Chile purchase this beverage to the Ica valley. The common eau-de-vie is called Pisco eau-de-vie because it is shipped from this port.” (Crónicas y Relaciones que se refieren al origen y virtudes del Pisco. Bebida Tradicional y Patrimonio del Perú. [Chronicles and relationships referring to the origin and virtues of Pisco. Peruvian traditional beverage and heritage] Banco Latino, 1990, First Edition, Lima, pag. 35).

Pisco,

the Peruvian grape eau-de-vie, rapidly gained prestige and its export

volumes grew significantly, as confirmed by the maritime trade news of

the 17th and 18th Centuries and the many testimonies and stories of

travelers in the 19th Century, which explain how the favorable

conditions of the Ica and Moquegua valleys and the techniques developed

by Peruvian craftsmen achieved a top-quality product that is now a

symbol of tradition and pride.

Pisco,

the Peruvian grape eau-de-vie, rapidly gained prestige and its export

volumes grew significantly, as confirmed by the maritime trade news of

the 17th and 18th Centuries and the many testimonies and stories of

travelers in the 19th Century, which explain how the favorable

conditions of the Ica and Moquegua valleys and the techniques developed

by Peruvian craftsmen achieved a top-quality product that is now a

symbol of tradition and pride.As mentioned above, the exports of Peruvian grape eau-de-vie were made by sea to different destinations of the Colony through the port of Pisco. However, one further aspect is that the Peruvian eau-de-vie was stored in the famous earthen jars manufactured since ancient times in the region and which, coincidentally enough, were called “Piskos”. These two fundamental elements explain how the name was permanently branded to the product.

The Peruvian origin of the Pisco appellation has been broadly recognized around the world. For example, the last edition of the Diccionario de la Lengua Española (Dictionary of the Spanish Language) defines pisco as "eau-de-vie originally manufactured in Pisco, a region in Peru.” Likewise, the Encyclopaedia Britannica defines the word pisco as "city, Ica, in the southwest of Peru... known by its brandy made of muscatel grapes."

pisco bilingual magazine

established culture, such as that celebrated by wine enthusiasts around the world. And, according to Livio Pastorino, editor of the monthly e-magazine, El Pisco es del Perú, not only does a culture of pisco need to be celebrated throughout Peru and the world, but also pisco lacks a transparent organization of authority on its quality, standards and production.

established culture, such as that celebrated by wine enthusiasts around the world. And, according to Livio Pastorino, editor of the monthly e-magazine, El Pisco es del Perú, not only does a culture of pisco need to be celebrated throughout Peru and the world, but also pisco lacks a transparent organization of authority on its quality, standards and production.

Preparation

Preparation

a numerous family. His infancy went by between school and collaborating in the restaurant that his father owned.

a numerous family. His infancy went by between school and collaborating in the restaurant that his father owned. that of the face of the traveler who gave her the letter.

that of the face of the traveler who gave her the letter. Don’t miss this interview in “Pisco Gatherings.” This month of June we have interviewed Mr.Carsten Korch, editor of www.livinginperu.com. Mr. Korch is Danish, has fallen in love with Peru and has created the website in English which is dedicated to bringing information on or country to the world. Very interesting!

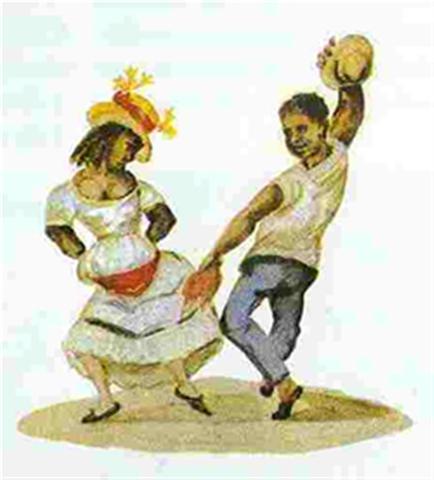

Don’t miss this interview in “Pisco Gatherings.” This month of June we have interviewed Mr.Carsten Korch, editor of www.livinginperu.com. Mr. Korch is Danish, has fallen in love with Peru and has created the website in English which is dedicated to bringing information on or country to the world. Very interesting! that you will only find in this valley in Arequipa. The sun rises in Caraveli when Don Pedro Ramirez’s melancholy violin changes the mood and gives a festive mystical essence to this colonial tradition in the Chirisco Estate. In the stone winery, under the eunich eyes of the music, the group of eight men stands ready for the first notes with which to begin, with enviable choreography, the traditional stomping of the grapes in the Caraveli valley. Dona Rosa Montoya, patron of the stomping of the grapes and of the Chirisco Bodega, is required by the musical duo (Luis Montoya on guitar) to choose the captain of the stomping. Leoncio Huamani is chosen with three moderate slaps on his backside with grape vines. He has participated for more than twenty years in the folklore of the wine and Pisco and he learned to stomp, he confesses from his father when he was a boy.

that you will only find in this valley in Arequipa. The sun rises in Caraveli when Don Pedro Ramirez’s melancholy violin changes the mood and gives a festive mystical essence to this colonial tradition in the Chirisco Estate. In the stone winery, under the eunich eyes of the music, the group of eight men stands ready for the first notes with which to begin, with enviable choreography, the traditional stomping of the grapes in the Caraveli valley. Dona Rosa Montoya, patron of the stomping of the grapes and of the Chirisco Bodega, is required by the musical duo (Luis Montoya on guitar) to choose the captain of the stomping. Leoncio Huamani is chosen with three moderate slaps on his backside with grape vines. He has participated for more than twenty years in the folklore of the wine and Pisco and he learned to stomp, he confesses from his father when he was a boy.